In the next six months, it’s likely that every American will be vaccinated, recovered from coronavirus infection, or both. If that happens, cases and deaths could decline, and the pandemic could start to fade.

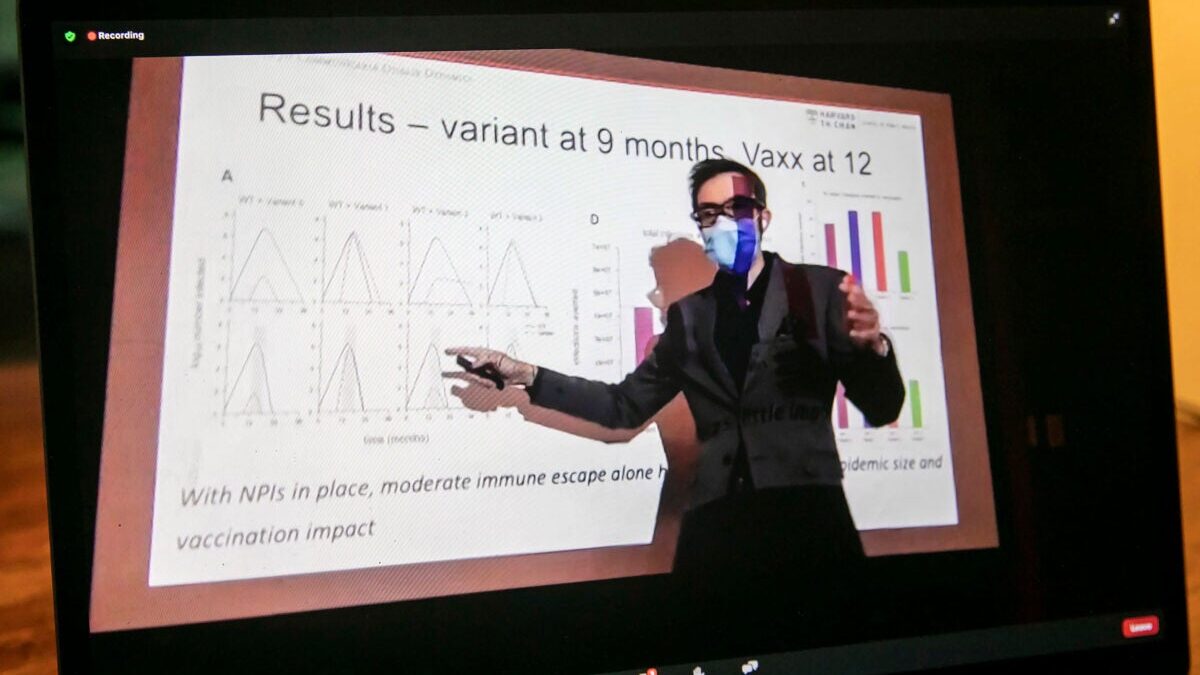

That’s what William Hanage predicted in a Thursday evening seminar titled “COVID-19: What we’ve learned about the pandemic and what we keep forgetting.” In his talk, Hanage, an associate professor of epidemiology at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and faculty member of the Center for Communicable Disease Dynamics, offered an optimistic outlook, predicting no significant winter surge and a steady drop in cases through March 2022. But, he said, the pandemic will wane only if the country learns from past mistakes, remains cautious, and relies on more interventions than just the vaccine. And, of course, if no new superspreading variant capable of breakthrough infections arises.

“Things could be relatively good, or they could not be,” he said.

Hanage uses both theoretical and laboratory work to track and predict the evolution of various infectious diseases. Since February 2020, he and other epidemiologists have used mathematical modeling to try to anticipate how COVID-19 might spread across the globe. Possible scenarios range from a single, controlled outbreak to an uncontrolled pandemic. Which way the world tips depends on two major factors: how infectious people are before they develop symptoms, and what measures countries use to control outbreaks.

As of February 2020, scientists already knew people carrying the virus were infectious before developing symptoms and that certain now-ubiquitous interventions — social distancing, wearing masks, washing hands — could help prevent the spread.

“It is remarkable how much we’ve forgot — it’s staggering,” Hanage said. “But we’ve also learned a lot.” The problem is, he continued, “Now we know and still do nothing.”

In early 2020, COVID-19-associated mortality correlated with crowding and population density, Hanage said. But by the time record cases and deaths swept through the Sun Belt between September 2020 and February 2021, causing 54 percent of the now nearly 700,000 total deaths in the U.S., those top correlations shifted. Although nursing homes remained the single biggest predictor of mortality, the second biggest was political leaning: Republican-run states, many of which enacted fewer control strategies, experienced the most devastating surges.

Today, those same states still resist the same tactics that might have prevented those surges, said Hanage, citing recent headlines such as the one that ran in Vanity Fair: “Mississippi Governor Announces Bold Plan to Do Nothing to Stop COVID.” As of September, Mississippi has the highest rate of deaths, with about one in every 320 succumbing to the virus.

Even in those same states, Hanage predicts no similar surge in the coming months, perhaps because of immunity built up in the last “grim winter,” he said. That immunity came at a high cost of infection, hospitalization, and death shouldn’t be forgotten.

And, Hanage warned, models — like weather forecasts — can be wrong.

If, for example, vaccination rates plateau at 80 percent, the remaining 20 percent of unvaccinated Americans can still fuel an outbreak as severe as the lethal surges in New York in spring 2020 or the summer 2021 spike in Florida. “The reason for that,” Hanage said of the Florida outbreak, “is the action not taken between then and now.” Even the most vulnerable population members — those 65 and older — still have lower-than-expected vaccination rates. An outbreak in that community could cause a moderate surge in the coming months. “These things really matter when we try to figure out why there are still 2,000 deaths a day,” said Hanage.

As the first speaker in this year’s Microbial Sciences Initiative’s Thursday Seminar Series, Hanage spoke from an on-campus lecture hall to a small, socially distant, in-person audience and a far larger virtual one. He said that vaccination may be the single most important factor to slow the pandemic, but it’s not the only one. Although he is vaccinated, in the on-campus lecture hall Hanage wore a mask, kept the windows open, and didn’t shake hands.

“People want one simple trick to end the pandemic,” he said. “And there isn’t one.” Like the now-famous “Swiss cheese model” of pandemic defense, which Hanage projected on screen, a multilayered defense works best.

Hanage also stressed the importance of wide-scale and rapid testing to help curb outbreaks and identify breakthrough cases in the vaccinated population. Epidemiologists are just now starting to study breakthrough cases and reinfections — two unpredictable factors that could affect how the pandemic shifts over the next six months. That, and it’s still possible a new variant (or “scariant,” Hanage said) could evolve to bypass the immunity afforded by vaccines, making it vital that even vaccinated people remain cautious.

“We cannot direct the wind,” read a quote Hanage projected to conclude his talk, “but we can adjust the sail.”